A Strategic Framework Proposal for Korean CBDC and Stablecoin

Structural Roles of CBDCs, Bank-Issued Stablecoins, and Non-Bank Stablecoins, and a Path to Institutionalization in Korea

- CBDCs and stablecoins are not substitutes but complements, reflecting a digital continuation of the traditional dual monetary system between central bank and commercial bank money.

- As demonstrated by initiatives like Project Agorá, CBDCs are essential for cross-border settlements in terms of legal finality, monetary sovereignty, and governance neutrality.

- Bank-issued stablecoins serve institutional use cases requiring wholesale settlement and regulatory trust, while non-bank stablecoins are optimized for the retail economy and the Web3 ecosystem, forming a parallel structure.

- To balance monetary sovereignty with innovation, Korea should pursue a dual-track approach: allowing non-bank stablecoin experiments within regulatory sandboxes, while promoting institutional stablecoins led by commercial banks.

Preface

This report explores the evolving architecture of digital currencies by analyzing the structural roles and potential coexistence of three core forms: central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), bank-issued stablecoins, and non-bank stablecoins. While the legacy two-tier monetary system—central bank money and commercial bank deposits—remains intact in the digital era, the emergence of privately issued digital currencies introduces a third axis, transforming the monetary landscape into a tripartite model.

Each type of digital currency differs fundamentally in its issuer, technical infrastructure, regulatory viability, and policy alignment. Rather than forcing convergence into a unified framework, the report advocates for a coexistence model grounded in functional differentiation and parallel architecture. Drawing from international case studies, we assess the public utility and technological boundaries of each currency type: CBDCs serve as tools for sovereign settlement and monetary control; bank-issued stablecoins facilitate the digital evolution of regulated finance; and non-bank stablecoins drive innovation across retail markets and Web3 ecosystems.

Given Korea’s policy priorities—monetary sovereignty, foreign exchange oversight, and financial stability—this report proposes a pragmatic strategy: promote bank-led stablecoins within the institutional framework while confining non-bank models to limited experimentation through regulatory sandboxes. It further argues for a hybrid architecture that ensures technical neutrality and interoperability between public and private blockchain systems, enabling seamless collaboration between traditional institutions and private innovation.

Ultimately, this report outlines a policy direction that allows Korea to pursue global regulatory alignment and technological modernization, while safeguarding the sustainability of its national monetary system.

0. Purpose and Scope of the Report

This report aims to analyze the global issuance and distribution models of digital assets that are framed as legal tender, and to propose a direction that Korean policymakers and industry stakeholders may consider in guiding institutional adoption and market development. Readers in other regulatory jurisdictions are encouraged to review this report with local context in mind.

In particular, the report seeks to clarify the frequently conflated concepts of CBDCs and stablecoins—both of which claim a 1:1 peg to fiat currency—and to redefine their respective roles and use cases. From this foundation, the report explores how CBDCs, bank-issued stablecoins, and non-bank-issued stablecoins can function as three complementary pillars of digital money in the on-chain financial era.

1. CBDC vs. Stablecoin

1.1. The Digital Transformation of the Dual Monetary System

Modern monetary systems have long been based on a dual structure: central bank-issued money (such as physical cash and reserves) and commercial bank-created money (such as deposits and loans). This architecture has balanced institutional trust with private-sector scalability. In the era of digital finance, this dual structure remains relevant—manifesting in the form of CBDC and bank-issued stablecoins. As digitization accelerates, a third pillar has emerged: non-bank stablecoins issued by fintech firms and crypto-native entities.

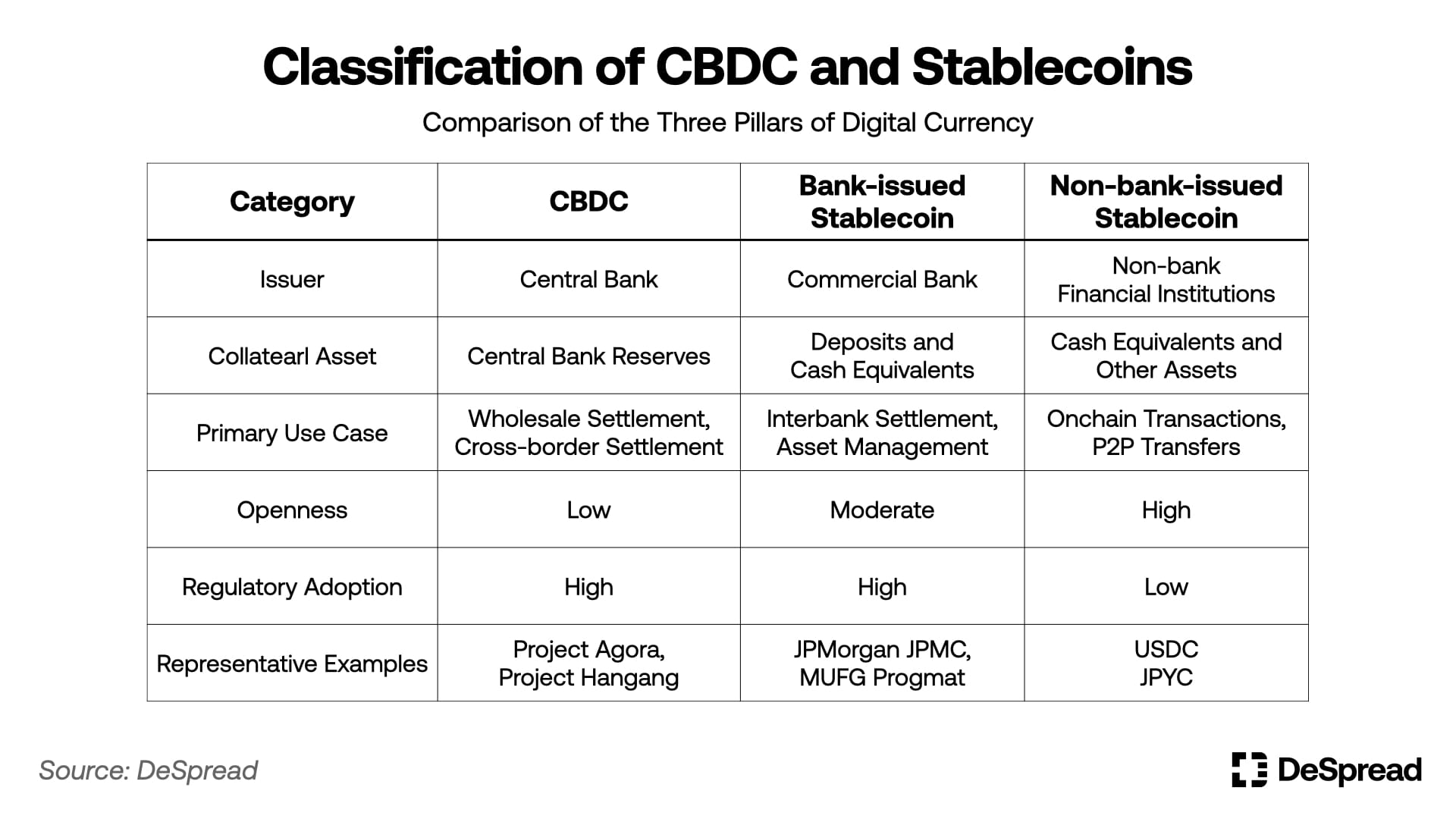

The resulting digital monetary landscape can be summarized as follows:

- CBDC: Digital currency issued by the central bank, designed to serve public policy objectives such as monetary control, financial stability, and the modernization of payment infrastructure.

- Bank-issued stablecoins: Digital tokens backed by customer deposits, government bonds, or cash held by commercial banks.(1) Deposit tokens are fully backed on a 1:1 basis by deposits, offering legal certainty and regulatory alignment.(2) Other variants may be backed by non-deposit assets (e.g., cash or sovereign bonds) and include models such as consortium-based stablecoin initiatives among banks.

- Non-bank stablecoins: Issued by entities outside the traditional banking sector, such as fintech or crypto companies. These typically circulate on public blockchains but increasingly take hybrid forms—partnering with trust banks or custodians to enhance deposit-backing and regulatory compatibility.

The BCG (2025) report categorizes digital currencies into three types—CBDCs, deposit tokens, and stablecoins—based on the nature of the issuer and the underlying collateral. CBDCs are base money issued by central banks and serve as instruments of public trust and final settlement. Deposit tokens represent commercial bank deposits tokenized on-chain, offering high interoperability with the existing financial system. In contrast, stablecoins are defined as privately issued digital assets backed by fiat currencies or government bonds, typically circulating in technology-native ecosystems outside traditional regulatory structures.

However, this typology does not always align with how individual jurisdictions design their regulatory frameworks. In Japan, the regulatory focus lies not on technical distinctions between deposit tokens and stablecoins, but rather on issuer type—bank versus non-bank. While the 2023 amendment to the Payment Services Act formally permitted stablecoin issuance, eligible issuers were limited to banks, money transfer operators, and trust companies. Moreover, eligible collateral was initially restricted to bank deposits, though recent discussions have considered allowing up to 50% of collateral in Japanese government bonds. This indicates a possible convergence of deposit tokens and stablecoins in practice, yet Japan’s bank-centric issuer framework diverges from the technology-based classification proposed by BCG.

In the United States, US dollar-based non-bank stablecoins have already captured significant market share and enjoy strong structural demand, making private-sector-driven classification models more relevant. In contrast, countries such as Korea and Japan, where no dominant digital token infrastructure currently exists, may find it more appropriate to focus on issuer trust and monetary policy compatibility as foundational criteria during early-stage regulatory design. This reflects a fundamental difference in policy philosophy beyond simple technical distinctions.

Accordingly, this report redefines digital currencies into three categories—CBDCs, bank-issued stablecoins, and non-bank stablecoins—based on their policy acceptability, the credibility of their issuance structures, and their alignment with national monetary objectives.

CBDCs and stablecoins must be understood not as substitutes, but as complementary components of a digital monetary ecosystem. Their differences extend far beyond technical implementation—they diverge fundamentally in their roles within the economic system, their capacity to support monetary policy, and the scope of financial stability and governance accountability.

That said, some jurisdictions are experimenting with new structural configurations. China’s e-CNY is designed as a direct monetary policy tool, India’s digital rupee supports a transition toward a cashless economy, and the UK’s Project Rosalind explores a retail CBDC model with direct consumer access.

In Korea, the Bank of Korea is also testing the boundaries between central bank money and digitized commercial bank deposits. Its “Project Hangang” pilots an integration mechanism between a wholesale CBDC, issued for institutional use, and deposit tokens, which represent a 1:1 digital conversion of commercial bank deposits. This experiment reflects a policy approach aimed not at creating a separate regime for private digital money, but at incorporating deposit tokenization into the CBDC framework itself.

Separately, in April 2025, Korea’s major commercial banks (KB, Shinhan, Woori, NongHyup, IBK, and Suhyup), along with the Korea Financial Telecommunications and Clearings Institute (KFTC), initiated a joint venture to issue a KRW stablecoin. This effort represents a different trajectory from deposit tokens—a private-sector driven digital currency initiative—and suggests that the regulatory distinction between deposit tokens and bank-issued stablecoins will become increasingly significant in Korea’s future institutional framework.

1.2. Global Adoption of Hybrid Models

Leading jurisdictions such as the United States, the European Union, and Japan—as well as international bodies like the BIS and IMF—are increasingly favoring a digital continuation of the dual monetary system. Notably, recent wholesale stablecoin initiatives under consideration by major U.S. banks (including BNY Mellon, U.S. Bank, and Citi) propose new infrastructure that enables real-time interbank settlement and collateral clearing without central bank involvement.

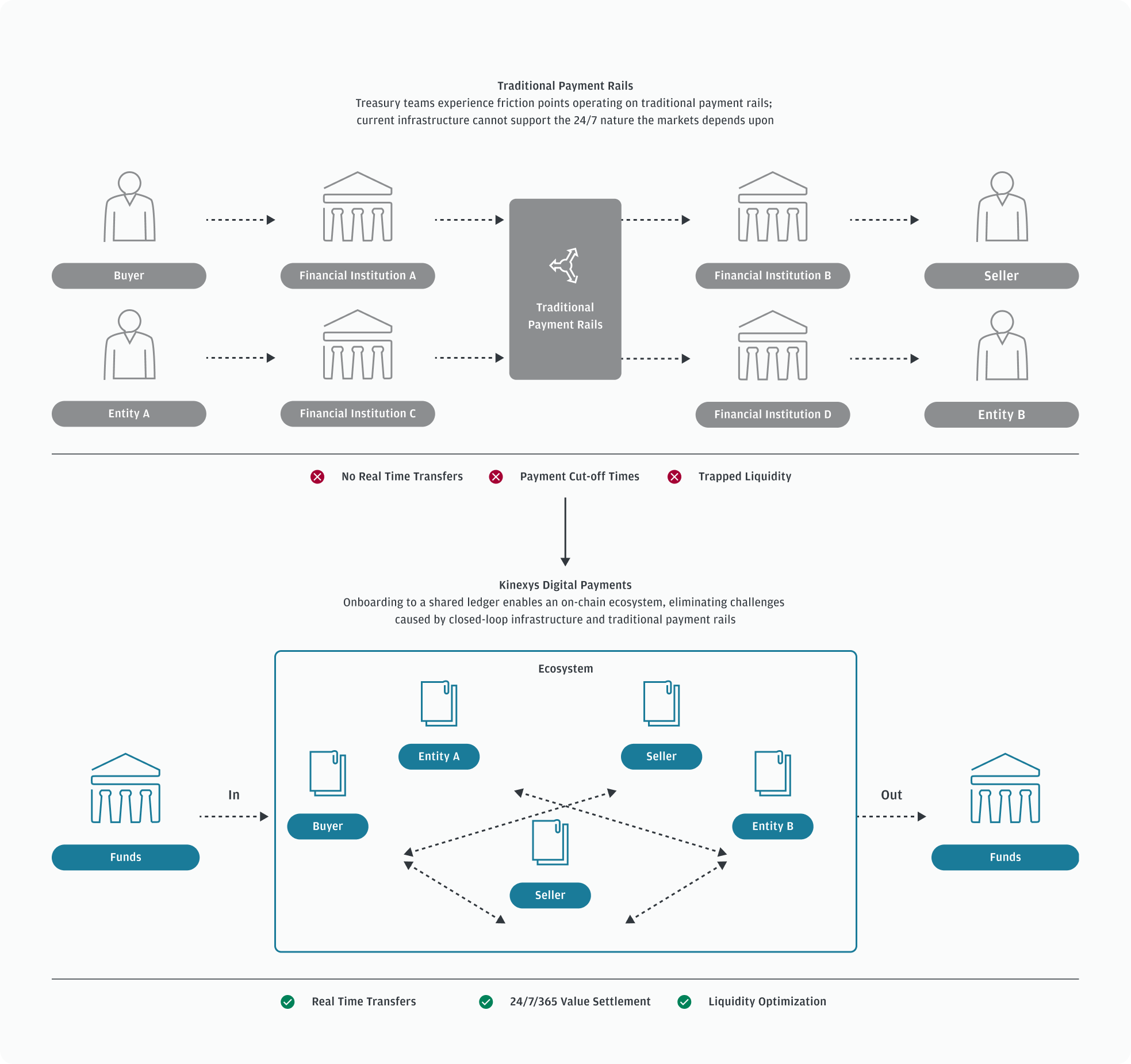

As noted in the BCG (2025) report, stablecoins that meet regulatory standards could offer a viable alternative for wholesale digital payment infrastructure, particularly in countries where the rollout of CBDCs is not imminent. This perspective aligns with emerging use cases such as JP Morgan’s Kinexys, Citi’s Regulated Liability Network (RLN), and Partior, which demonstrate that private-sector infrastructures can support high-trust digital settlement even in the absence of a CBDC.

1.3. Reassessing the Need for CBDCs

As wholesale stablecoins issued by commercial banks continue to gain traction as a means of building efficient settlement infrastructure, it is reasonable to ask:

“Are CBDCs still necessary?”

Our answer is a firm yes. The limitations of private models go beyond technical maturity or commercial reach. They face fundamental constraints in fulfilling public functions—such as enabling monetary policy execution, providing legal finality, and ensuring neutrality in cross-border settlement.

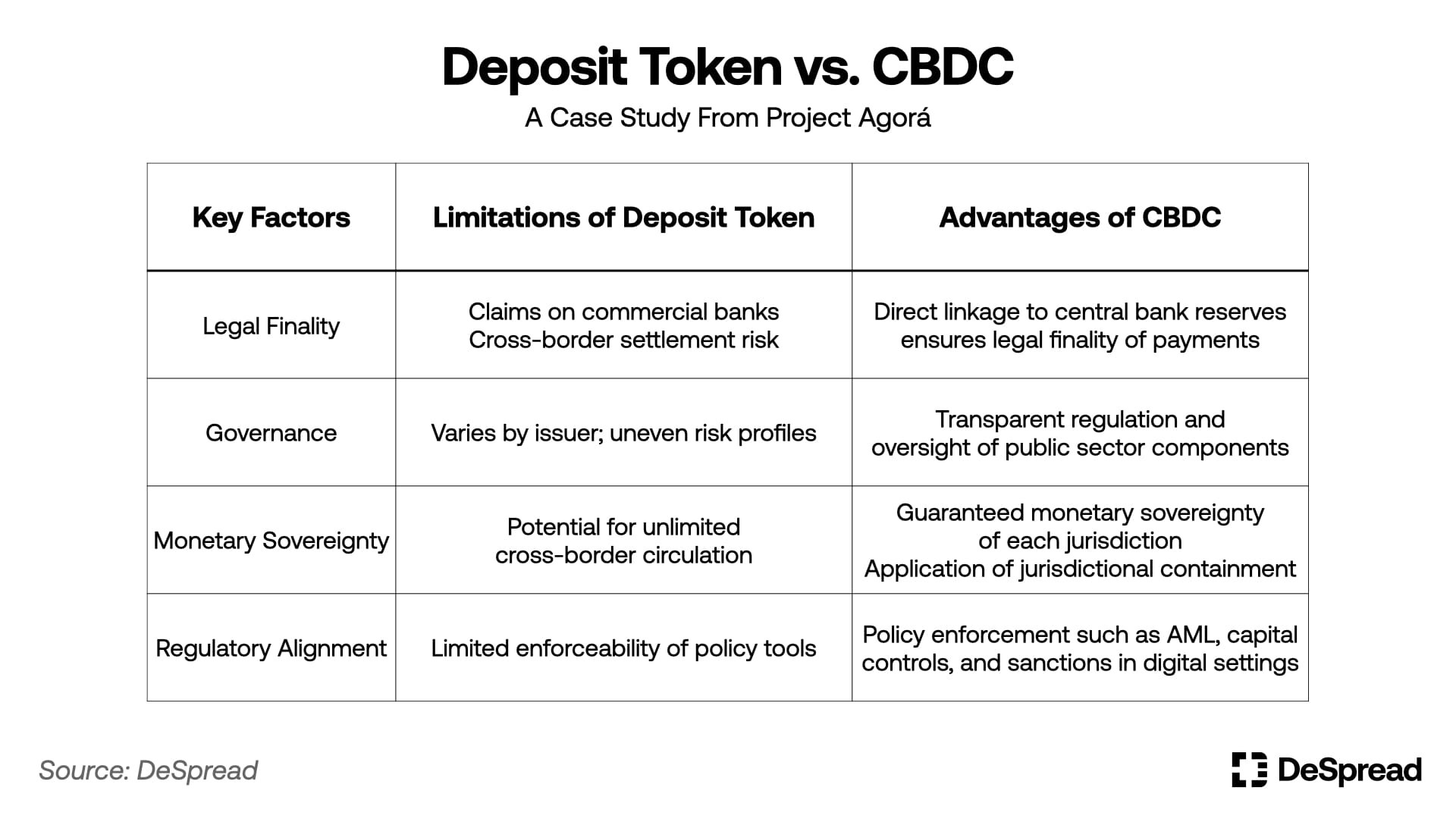

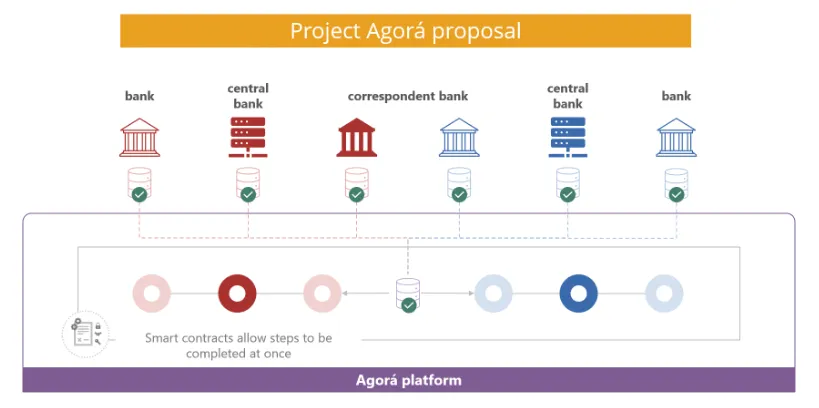

One of the most notable policy experiments addressing these issues is Project Agorá (2024), a collaborative initiative involving the BIS, ECB, MAS, IMF, and central banks from seven jurisdictions, along with multiple global commercial banks. The project tested a model in which CBDCs and deposit tokens operate in parallel within a cross-border wholesale settlement system. It aimed to develop design principles that promote interoperability between public (CBDC) and private (deposit token) money, while preserving regulatory control and monetary sovereignty.

The project offers several implicit policy insights:

- Legal Finality Project Agorá emphasized that CBDCs, being liabilities of the central bank, provide intrinsic legal finality in settlement. In contrast, deposit tokens represent claims on commercial banks, which may carry legal ambiguity—particularly in cross-border transactions where finality is essential.

- Asymmetric Governance CBDCs are governed under transparent public-sector rules and oversight, whereas privately issued tokens operate within varying technical frameworks and governance models. This asymmetry introduces risk, especially in multilateral currency exchange systems.

- Monetary Sovereignty and Jurisdictional Containment Agorá’s architecture restricted the use of deposit tokens to the financial system of the issuing country, preventing extraterritorial circulation. This was designed to protect national monetary policy from the unchecked expansion of private digital currencies across borders.

- Regulatory Alignment and Policy Integration The BIS examined how regulatory tools—such as AML, FX controls, and capital flow restrictions—can be integrated into digital settlement layers. CBDCs, as public money, inherently support such integration, providing a distinct advantage over private alternatives.

Ultimately, the significance of Project Agorá lies in its dual-layered architecture that clearly delineates roles and limitations: CBDCs serve as instruments of public trust and regulatory harmonization in cross-border digital settlements, while deposit tokens act as agile transactional interfaces for commercial entities.

This architectural clarity is especially important for countries like Korea, where sensitivity to monetary sovereignty remains high. The Bank of Korea actively participated in Project Agorá, experimenting with deposit token-based digital settlements. At the “8th Blockchain Leaders Club” on May 27, Bank of Korea Deputy Governor Lee Jong-Ryeol emphasized that Korea’s deposit token is explicitly designed to be non-transferable outside national borders, and that preserving monetary sovereignty is central to the Agorá framework (source). This underscores Korea’s commitment not only to technological adoption, but also to safeguarding sovereign control within digital financial infrastructures.

Whereas Project Agorá demonstrated the coexistence model between CBDCs and deposit tokens in international settlements, Project Pine—a 2025 initiative by the BIS and the Reserve Bank of Australia—validated the use of CBDCs as tools for executing monetary policy and provisioning liquidity in programmable environments.

In Project Pine, the central bank used smart contracts to automatically provide conditional liquidity against tokenized government bonds as collateral. The experiment went beyond mere token transfers and showcased how a central bank could dynamically inject or withdraw liquidity in real time and digitally modulate the money supply through on-chain infrastructure.

This represents a shift from traditional interest rate signaling toward a future where monetary policy execution is automated via smart contracts—effectively “codifying” central bank governance. In this context, CBDCs are not merely payment instruments, but programmable infrastructures that enable central banks to conduct policy with precision, transparency, and automation.

1.4. A Parallel Framework of CBDCs and Stablecoins as the New Monetary Paradigm

CBDCs should not be viewed merely as "public sector stablecoins." Rather, they represent a core pillar of the digital financial era—functioning as tools for policy execution, settlement infrastructure, and institutional trust. In contrast, private stablecoins are better understood as agile and demand-driven financial instruments tailored to specific use cases and user needs.

The essential question is not “Why do we need both?”—but rather recognizing that we already live within a dual monetary system, where central bank money and commercial bank money coexist. That structural paradigm will persist in the digital age, even if the underlying technologies change.

A parallel architecture of CBDCs and private stablecoins is thus not an anomaly, but rather the foundation of a new monetary policy order for the digital era.

2. Bank vs. Non-Bank Stablecoin

As the parallel coexistence of CBDCs and private stablecoins becomes accepted as a policy framework, the debate is now shifting to the next level of granularity:

Should we institutionalize both bank-issued and non-bank-issued stablecoins as distinct instruments? Or should regulatory frameworks formalize only one and exclude the other?

Although both types of stablecoins maintain a 1:1 peg to fiat currency, they differ fundamentally in issuer identity, policy compatibility, technical infrastructure, and target use cases. Bank-issued stablecoins are created by regulated financial institutions using customer deposits or sovereign bonds, and are often implemented in permissioned or private blockchain environments.

In contrast, non-bank stablecoins are typically deployed on public blockchains and issued by Web3-native companies, fintech startups, or global crypto organizations.

2.1. The Role of Bank-Issued Stablecoins: On-Chain Automation of Regulated Finance

Bank-issued stablecoins aim to replicate the function of traditional deposits within the regulated financial system—but on-chain. Examples such as JPM Coin by JP Morgan, Progmat Coin by MUFG, the JPY stablecoin by SMBC, and Citi’s Regulated Liability Network (RLN) are all account-based digital tokens issued under strict regulatory frameworks, including AML/KYC compliance, deposit insurance, and capital adequacy standards.

These stablecoins are utilized in institutional contexts for DvP (Delivery versus Payment) and FvP (Free versus Payment) settlement, cross-border trade finance, and portfolio operations. They offer legal finality, KYC-based participant control, and the potential for central bank reserve linkage—combining institutional stability with the automation flexibility of smart contracts to serve as programmable digital cash.

Notably, JP Morgan’s Kinexys and Citi’s RLN operate on permissioned networks, not public blockchains. Transactions are only permitted between pre-verified institutions with known identities, defined transaction purposes, and source-of-funds validation, ensuring clear legal liability and regulatory alignment.

These networks use a centralized node structure and interbank consensus protocols to enable real-time payment and settlement, allowing regulated on-chain financial operations without exposure to the volatility and compliance risks often associated with public blockchains.

In major economies such as the United States, Japan, and South Korea, commercial banks are either already issuing or actively pursuing the issuance of deposit-backed stablecoins. Beyond deposit-based models, stablecoins backed by liquid assets such as government bonds and money market funds (MMFs) are also being signaled at a multinational level. In the U.S., major banking consortia such as Zelle and The Clearing House are discussing the joint issuance of stablecoins, foreshadowing the broader adoption of regulated stablecoin models issued by commercial banks.

Japan’s Financial Services Agency is considering allowing up to 50% of stablecoin reserves to be held in government bonds. In South Korea, six major commercial banks—KB Kookmin, Shinhan, Woori, NongHyup, IBK, and Suhyup—along with KFTC, are jointly establishing a legal entity to issue a Korean won stablecoin. This initiative runs in parallel with the Bank of Korea’s wholesale CBDC pilot project (Project Hangang), indicating a potential coexistence between deposit tokens and stablecoins.

These developments suggest that the tokenization of deposits is evolving beyond technical experimentation, introducing real automation into the settlement and clearing infrastructure of traditional finance. At the same time, major economies are attempting to expand the eligible collateral base of bank-issued stablecoins to include highly liquid assets—thereby reinforcing their role as regulated liquidity instruments within the financial system.

2.2. The Role of Non-Bank Stablecoins: General-Purpose Digital Currency for the Retail Economy

In contrast, non-bank stablecoins have emerged as a new user interface for digital money—driven by technological innovation and global scalability. Leading examples include USDC by Circle, PYUSD by PayPal, and XSGD by StraitsX. These tokens are widely used in e-commerce payments, DeFi transactions, DAO incentives, in-game item trading, and peer-to-peer remittances, serving as programmable digital cash in micro-payment environments. Operating freely on public blockchains, they offer accessibility and liquidity beyond the traditional financial system—often functioning as the de facto currency standard in Web3 and DeFi ecosystems.

The non-bank stablecoin sector itself consists of two divergent models.

One branch is committed to disruptive innovation, operating entirely outside traditional financial rails and leveraging the openness of public blockchain infrastructure.

The other seeks regulatory legitimacy and integration, pursuing licensing pathways such as MiCA compliance in Europe and alignment with U.S. financial regulators.

Firms like Circle exemplify this second path, while community-driven, decentralization-first projects continue to experiment at the frontier.

As such, non-bank stablecoins exist within a dynamic tension between innovation and institutionalization. The ultimate policy framework—whether accommodating or restrictive—will play a critical role in determining how these two directions are balanced in the market.

2.3. Optimistic View: Functional and Policy-Based Differentiation Enables Coexistence

Rather than posing the question of whether bank- and non-bank-issued stablecoins are technically interchangeable, it is more productive to examine their coexistence through a political, functional, and industrial-strategic lens. Each model has distinct constraints and use cases, supporting the increasingly credible view that they can coexist in differentiated roles.

Bank-issued stablecoins are used primarily in institutional transactions, asset management, and wholesale settlement, benefiting from legal certainty and regulatory oversight. JP Morgan’s Kinexys has been in active operation for over four years, while Citi’s RLN and MUFG’s Progmat Coin are progressing through live validation phases.

In contrast, non-bank stablecoins serve as digital cash for micro-payments, global retail services, on-chain incentive systems, and decentralized applications (dApps). They are the de facto standard currency across public blockchain environments.

Importantly, non-bank stablecoins play a critical role in advancing digital financial inclusion and innovation—especially for underserved or unbanked populations. Accessing bank-issued stablecoins typically requires identification, residency, credit history, and minimum deposits, creating high entry barriers. In contrast, public chain-based stablecoins offer a radically different interface: anyone with a digital wallet can participate, regardless of geography or financial status.

In this way, non-bank stablecoins represent a unique and irreplaceable interface for democratizing access to finance, especially in areas beyond the reach of traditional banking systems.

While bank-issued stablecoins are generally not deployed on public blockchains, this is not merely a technical preference but reflects a deeper regulatory disincentive toward permitting non-bank stablecoins on public networks. For regulators, anonymity, lack of traceability, and absence of off-ramp controls are seen as critical risks. As such, any digital currency that hopes to be institutionally accepted must feature a programmable degree of control and exit oversight. The logic of “censorship resistance” inherent in public blockchain maximalism is fundamentally at odds with existing financial regulation.

Nevertheless, the non-bank stablecoin landscape comprises a spectrum—ranging from disruption-focused protocols to regulatory-compliant issuers. This reflects an industry model where incremental institutionalization and experimental innovation coexist.

A notable step toward regulatory accommodation is the GENIUS Act, which recently passed a cloture vote in the U.S. Senate. The bill provides a framework for conditionally approving non-bank stablecoin issuance, thereby legitimizing market entry for innovative financial firms. Circle, for instance, is actively transitioning to a compliant model via the EU’s MiCA framework and coordination with U.S. regulators. In Japan, JPYC is partnering with MUFG to transition from a prepaid instrument to a regulated e-money format—highlighting the growing policy feasibility of non-financial issuers.

The emergence of smart contract–enabled stablecoins—capable of enforcing AML/KYC, geographic restrictions, and programmable transaction conditions—offers a path toward public blockchain–based tokens that align with regulatory expectations. However, technical complexity and institutional hesitation around public chain deployment remain unresolved challenges.

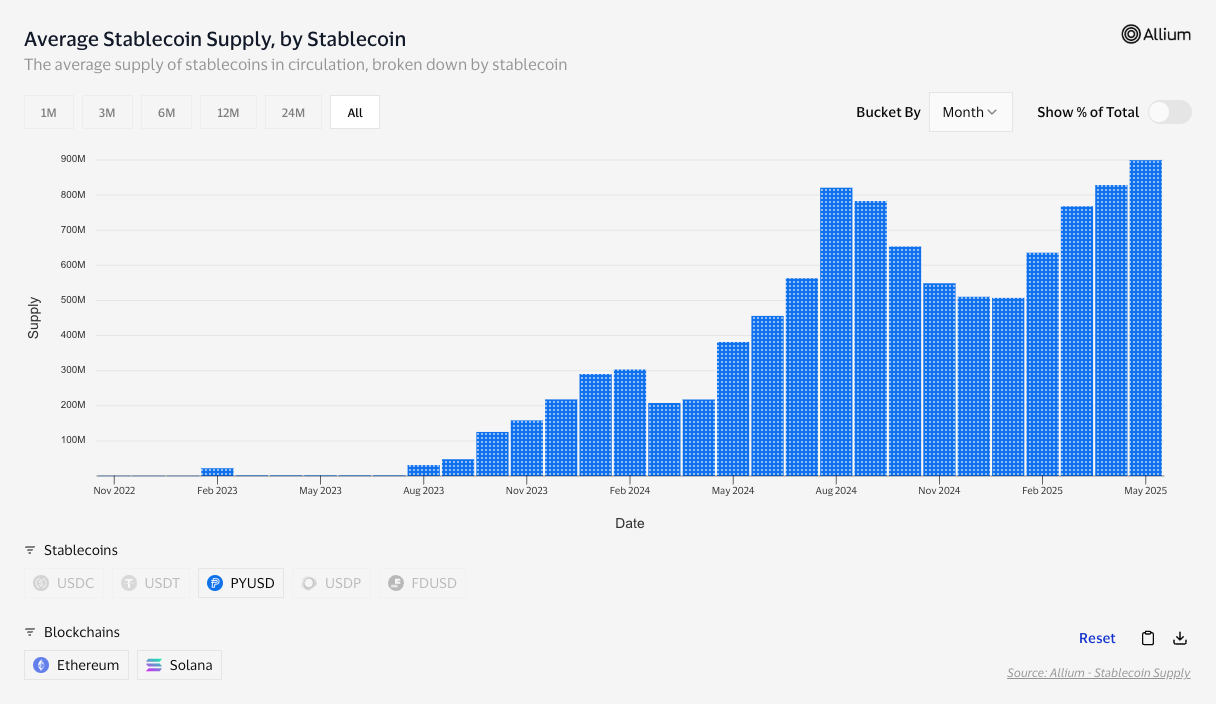

In this context, the model exemplified by PayPal and Paxos's PYUSD is especially noteworthy. PYUSD is issued and transacted on public chains like Ethereum and Solana, yet achieves compliance through Paxos’s fully collateralized dollar reserves and PayPal’s oversight of KYC and transaction monitoring. Since 2024, PYUSD has been gaining traction in both DeFi protocols and retail applications, demonstrating the viability of a regulatory-aligned, open-access stablecoin.

At a National Assembly policy forum held in May 2025, Minseop Yoon, Director of the Korea Consumer Finance Institute, emphasized that “the innovative potential of stablecoins stems from the participation of diverse players, including fintech and IT companies.” He also proposed a multi-layered regulatory strategy for their integration. This trend is further evidenced by Korean fintech firms such as Kakao Pay, which are currently exploring blockchain-based payment mechanisms, as well as ongoing regulatory discussions by the Financial Services Commission on stablecoins.

Importantly, this scenario should not be seen as a confrontation or replacement of the traditional financial system by non-bank stablecoins. Instead, these tokens complement areas that existing institutions have yet to fully embrace, indicating a strong case for coexistence.

Key areas—financial inclusion for the unbanked, practical utility within the Web3 ecosystem, and fast, low-cost global payments—cannot be fully realized through bank-issued stablecoins alone. Therefore, the emergence of both models should be understood as a functional divergence based on differentiated use cases, not as a matter of competition, but as a balance of complementary roles.

2.4. Pessimistic View: Traditional Industry May Absorb Disruptive Innovation and Reshape the Market

The current state of “functional coexistence” may prove unsustainable. Historically, technologies that once disrupted lower segments of the market have often been absorbed and reorganized by incumbent industries over time. Stablecoins are no exception—legacy institutions are taking them seriously and are already moving.

In the U.S., major banks have initiated preliminary discussions on launching a joint stablecoin project through Zelle and The Clearing House. In response to the potential passage of the GENIUS Act, these institutions are strategizing to preemptively address potential losses in FX fees, retail payment commissions, and control over user wallets by issuing their own stablecoins source.

In this scenario, non-bank stablecoins—even if they achieve technological superiority or wide user adoption—may ultimately be marginalized or absorbed by bank-led infrastructures. Given their ability to use central bank reserves as collateral, bank-issued stablecoins are likely to enjoy structural advantages in trust and efficiency over privately collateralized alternatives. This implies that public chain–based stablecoins may fall behind in institutional adoption and collateral credibility.

Global financial giants like Visa, Stripe, and BlackRock are not issuing their own stablecoins but are absorbing stablecoin technologies by integrating USDC into payment networks or launching tokenized funds like BUIDL, thereby redefining digital currency innovation within existing regulatory frameworks. This reflects a strategic move to harness innovation while preserving traditional financial trust and stability.

The case of StraitsX’s XSGD is emblematic of this trend. Though issued by a non-bank institution, XSGD is backed 1:1 by deposits at DBS and Standard Chartered, and operates on a closed network infrastructure via Avalanche Subnet.

Subnet: An enterprise-optimized network architecture that allows full customization of openness, consensus mechanisms, and privacy—designed to align with regulatory requirements.

Especially in the case of XSGD, it has been issued on Avalanche C-chain and is publicly available across various networks. However, this is a unique outcome enabled by Singapore’s open regulatory stance. In countries with more conservative regulatory frameworks, such a model would be difficult to replicate, likely restricting not only issuance but also distribution channels to permissioned environments. In this sense, XSGD symbolizes a compromise between regulatory legitimacy and blockchain openness, but in more risk-averse jurisdictions, it may instead reinforce the dominance of bank-issued models.

JP Morgan, through its Kinexys platform, has made it clear that all asset management and settlement will ultimately converge within a bank-controlled digital financial network. Similarly, BCG has emphasized that public chain–based stablecoins face structural limits in regulatory acceptance, arguing that only institution-led models can survive long-term within regulated financial systems.

Although Europe’s MiCA framework appears open to all issuers in principle, in practice it imposes capital thresholds, collateral requirements, and issuance caps that functionally exclude non-financial entities. Aside from Circle’s ongoing licensing effort, very few e-money token registrations have materialized as of May 2025.

In Japan, revisions to the Payment Services Act in 2023 have restricted stablecoin issuance to banks, trust companies, and licensed money transfer agents, and public chain–based tokens are only allowed on exchanges—not as recognized means of payment.

While the previously discussed “programmable compliance-friendly stablecoins” may appear to offer a middle ground, actual implementation is fraught with complex institutional challenges—including cross-border regulatory alignment, legal recognition of smart contracts, and attribution of risk and liability. Even if technically feasible, regulators will still prioritize issuers' credibility, capital adequacy, and operational control.

Ultimately, regulation-compliant non-bank stablecoins may end up operating like banks. In such a scenario, the original innovation of decentralization, inclusiveness, and censorship resistance inherent to public blockchains could be severely diluted. Therefore, the optimistic view that functional coexistence will continue indefinitely may be overly idealistic, and digital currency infrastructures are likely to consolidate around entities with scale, trust, and regulatory legitimacy.

3. A Strategic Framework Proposal for Korea's Stablecoin

3.1. Policy Environment and Foundational Premises

South Korea is a country with strong policy priorities around monetary sovereignty, foreign exchange controls, and financial supervision. The Bank of Korea has long relied on interest rate–based monetary policy as a primary mechanism for managing liquidity, emphasizing predictability and stability through policy rate signaling. Within this framework, the emergence of new forms of digital liquidity raises concerns about potential disruption to the traditional monetary transmission mechanism.

For instance, stablecoins issued by non-bank entities and backed by government bonds may perform monetary functions on-chain without being anchored to central bank base money (M0). These digital cash-like assets circulating outside the formal financial system can effectively constitute private sector money creation, potentially evading monetary aggregates like M1 and M2 and distorting the interest rate transmission pathway. As a result, authorities may classify such phenomena as “shadow liquidity.”

These concerns are not unique to Korea. International institutions have repeatedly raised similar alarms. The Financial Stability Board (FSB, 2023) warned that unchecked expansion of stablecoins could pose systemic risks to financial stability—highlighting cross-border liquidity transfers, AML/CFT evasion, and weakened monetary policy effectiveness as key concerns. Likewise, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS, 2024) noted that in some emerging markets, stablecoins have contributed to informal dollarization and capital flight from traditional bank deposits, thereby undermining monetary policy.

The United States is responding to these policy concerns with a pragmatic regulatory approach embodied in the GENIUS Act. The proposed legislation permits the issuance of privately issued stablecoins, but only under strict conditions—including high-quality collateral requirements, mandatory federal registration, and issuer eligibility criteria. Rather than disregarding warnings from the FSB and BIS, this represents a strategic effort to internalize and manage associated risks within a regulatory perimeter.

The Bank of Korea has also made its position on these policy risks increasingly clear. In a press conference held on May 29, 2025, Governor Rhee Chang-yong stated that “stablecoins are substitutes for sovereign currency issued by the private sector, and as such, may undermine the effectiveness of monetary policy.” He further expressed concerns that KRW-based stablecoins could lead to capital flight, weaken confidence in domestic payment systems, and provide a means to circumvent financial supervision. Rhee emphasized that any experimentation should start within the banking sector, where risks can be properly supervised.

Nonetheless, the Bank of Korea has stopped short of calling for a full prohibition. Instead, it appears to favor an approach that allows for experimentation under controlled conditions, thereby exploring the path to gradual institutionalization. In addition to its ongoing research on a central bank digital currency (CBDC), the Bank is also supporting commercial bank-issued deposit token experiments—such as “Project Hangang”—as a conditional way to enable private sector involvement in digital liquidity.

In sum, stablecoins represent a potential new variable in the transmission of monetary policy. The concern raised by global and domestic institutions is not about their technological feasibility, but about the terms under which such instruments can be accommodated within the existing monetary system. Therefore, Korea’s stablecoin strategy must not default to unbounded openness or technology-driven designs, but rather incorporate both policy safeguards and technical constraints as prerequisites for regulatory acceptance.

3.2. Policy Considerations on Stablecoins Backed by Cash-like Assets

3.2.1. Implications for Monetary Policy

Stablecoins backed by cash-like assets such as government bonds may appear to be safe, asset-backed digital currencies. However, from a monetary policy perspective, they represent a form of private money issuance outside the direct control of central banks. These instruments can bypass the traditional channels of base money (M0) while generating liquidity similar to broad money (M2), potentially undermining monetary authorities' influence.

Traditionally, the Bank of Korea has managed monetary policy by adjusting the policy rate to influence deposit rates and credit supply within the banking system—thereby indirectly controlling broad money. However, stablecoins collateralized by highly liquid assets could allow non-bank entities to inject liquidity directly into the economy, independent of the monetary transmission mechanism. These issuers operate outside conventional monetary controls such as capital adequacy, liquidity coverage ratios, or reserve requirements, posing a structural risk to central banks.

Moreover, government bonds are intended to serve as tools for settling liquidity already issued through fiscal policy. When such instruments are used again as collateral for issuing additional liquidity in the form of stablecoins, it effectively creates a "dual issuance" structure—currency issued without central bank authorization. This may expand market liquidity independently of the policy rate, weakening the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission.

According to empirical research by the BIS (2025), capital inflows into stablecoins are associated with a 2–2.5 basis point decline in the yield of 3-month U.S. Treasury bills within 10 days, while outflows cause an asymmetric increase of 6–8 basis points. This suggests that in short-term funding markets, interest rates may increasingly be shaped by liquidity flows from stablecoins—prior to central bank policy signals. Such a dynamic risks undermining the forward-looking influence of benchmark rates in anchoring market expectations.

This phenomenon can also extend to real interest rates. As liquidity created by stablecoins begins to affect asset prices and short-term interest rates within the financial system, the policy effectiveness of interest rate adjustments weakens. Ultimately, the central bank faces the risk of being relegated from a rate-setter to a market follower.

That said, not all stablecoins backed by government bonds pose an immediate or systemic threat to monetary policy. In fact, in April 2025, the U.S. Treasury characterized such instruments as part of a “digital transformation of existing monetary assets,” asserting that they do not affect the total money supply. Accordingly, the impact of these stablecoins varies depending on their design and the surrounding policy framework. A one-size-fits-all judgment is therefore inappropriate; what’s needed is a precise structural assessment.

In conclusion, stablecoins collateralized by government securities embody both risks and potential utility. Whether they can be institutionally accepted hinges on their ability to align with the existing monetary system—without undermining the predictability and credibility of monetary policy tools.

3.2.2. Global Comparison

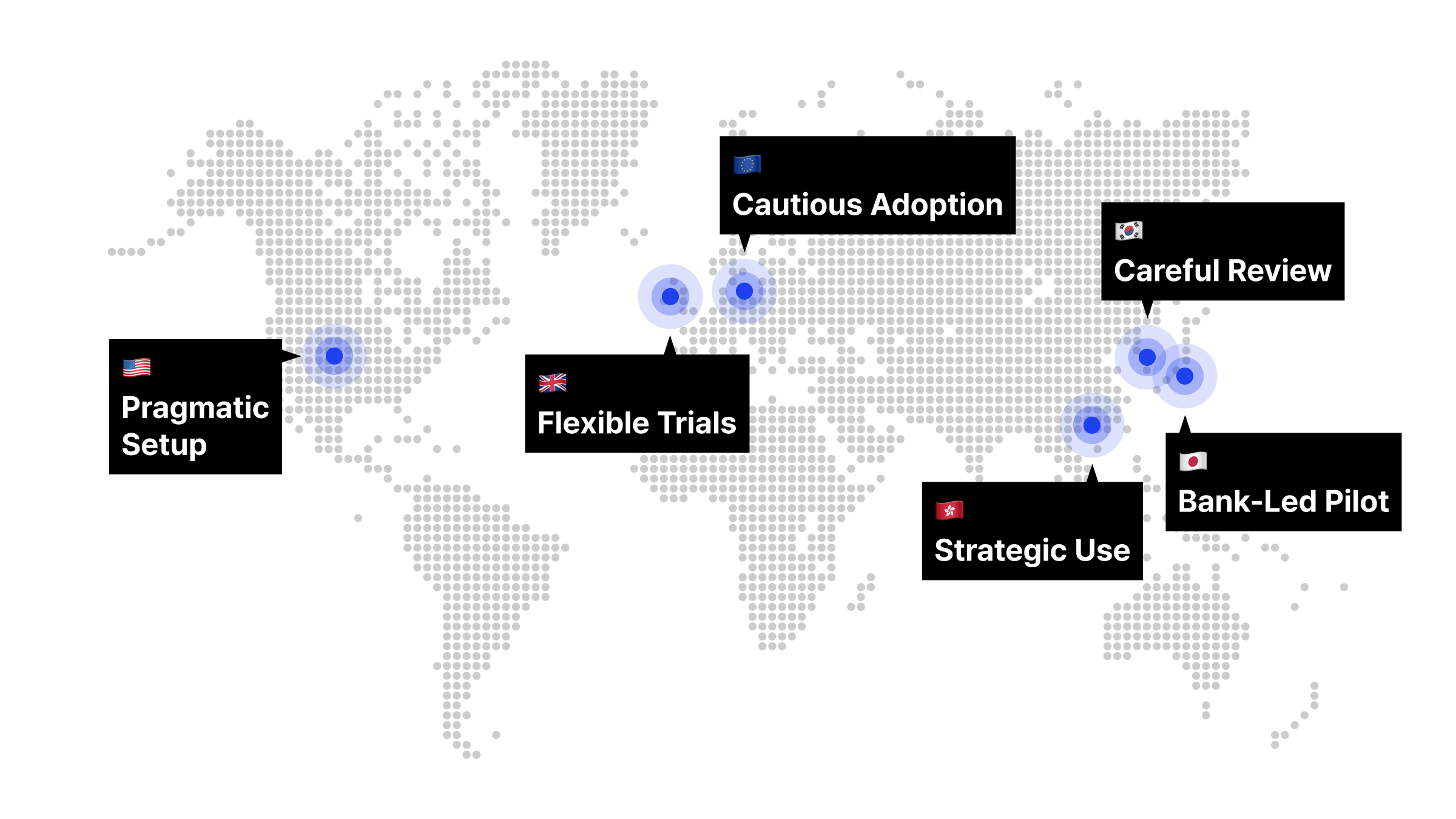

Policy responses to stablecoins backed by cash-equivalent assets vary across countries, shaped by differences in monetary system architecture, the depth of capital markets, the complexity of interest rate transmission mechanisms, and regulatory philosophy toward digital assets. The United States, Europe, Japan, and Korea each present a distinct approach to reconciling stablecoin institutionalization with monetary policy frameworks.

- United States: Given its deep capital markets and multi-layered interest rate transmission structure—encompassing the Federal Reserve, money market funds, and depository institutions—there is a growing perception that stablecoins collateralized by government bonds do not pose an immediate threat to monetary policy. Instruments such as Circle’s USDC, BlackRock’s sBUIDL, and Ondo’s tokenized T-bill funds illustrate an emerging architecture that integrates digital assets with money market liquidity. The recently proposed GENIUS Act aims to formalize the status of private stablecoins under regulatory oversight, subject to high-quality collateral requirements and mandatory issuer registration.

- Europe: The European Central Bank (ECB) adopts a more conservative and restrictive stance toward private stablecoins. Under the MiCA framework, stringent requirements are imposed on capital adequacy, redemption rights, and collateral transparency, effectively limiting stablecoin issuance to licensed financial institutions. The ECB remains cautious of stablecoins as potential substitutes for the digital euro and as unofficial channels that could undermine monetary policy. As a result, institutional stability is prioritized over technical experimentation.

- Japan: Owing to its ultra-low interest rate environment and bank-centric credit creation model, Japan has limited room for conventional monetary policy maneuvering. Consequently, there is a growing trend toward accepting private stablecoins as a complementary tool for digital credit expansion. Bank-issued models dominate policy discussions, and frameworks are under consideration that would require issuers to hold a portion of reserves in government bonds and issue stablecoins collateralized accordingly. Japan favors permissioned blockchain infrastructures and focuses on building a regulatory-compliant ecosystem.

- Korea: Due to Korea’s interest rate-centered monetary policy framework and relatively shallow capital markets, the Bank of Korea (BOK) has expressed significant concerns about the potential monetary policy implications of government bond-backed stablecoins. Since 2023, the BOK has repeatedly warned that “unanticipated inflows of digital currency could undermine the credibility of monetary policy, which is currently driven by the policy rate.” In May 2025, Governor Rhee Chang-yong emphasized that “privately issued stablecoins can function similarly to money, and issuance by non-bank institutions requires caution.” Currently, Korea is conducting wholesale CBDC pilots in parallel with experiments involving bank-issued deposit token payment systems.

- United Kingdom: In a May 2025 consultation paper, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) indicated a willingness to allow both short-term and certain long-term government bonds as eligible collateral for stablecoins. This move is seen as a regulatory experiment that grants issuers broader discretion over collateral composition, promoting market flexibility and private sector autonomy.

- Hong Kong: Hong Kong presents a particularly interesting case. Under its existing HKD-USD currency peg, regulators allow USD-denominated assets such as U.S. Treasuries to serve as collateral for stablecoins. This is not just a financial innovation initiative, but also a strategic extension of Hong Kong’s foreign exchange architecture. By embedding the peg system into digital liquidity frameworks, authorities appear to be reinforcing HKD-USD linkage through stablecoin infrastructure.

The scope of permissible stablecoins and the design of their collateral structures are not merely questions of risk tolerance. They often reflect broader policy goals regarding how digital currencies are intended to serve national priorities. Some jurisdictions prioritize monetary sovereignty and financial stability, while others aim to accommodate competitive innovation and strategic currency distribution. These variations suggest that digital currency policies are unlikely to converge into a single global model, but rather evolve into layered structures informed by institutional traditions and regulatory objectives.

3.3. Promoting Bank-Issued Stablecoins

3.3.1. Institutional Role and the Significance of Deposit-Backed Stablecoins

Deposit-backed stablecoins issued by commercial banks—often referred to as “deposit tokens”—are widely regarded by policymakers as one of the most trustworthy forms of digital liquidity. Because they are issued against existing deposit balances, they enable digital circulation without expanding the monetary base or distorting interest rate policy, making them a highly acceptable model within regulatory frameworks.

However, deposit-backed stablecoins are not without risk. Considerations such as bank liquidity risk, capital adequacy, and the potential use of such tokens beyond the scope of deposit insurance protections must be addressed in regulatory design. In particular, if large-scale on-chain distribution occurs, it could affect interbank liquidity structures and the functioning of payment systems. A complementary risk-based supervisory approach is therefore essential.

Despite these risks, policymakers generally take a favorable stance toward deposit-backed stablecoins for the following reasons:

- They are aligned with deposit protection schemes, enhancing consumer safeguards.

- They can be managed within the scope of reserve requirements and interest rate policy.

- Under commercial bank supervision, they facilitate compliance with AML/CFT and foreign exchange regulations.

Some argue that non-bank, government bond–backed stablecoins can drive innovation in the fintech ecosystem. However, many of these innovations can be achieved within a bank-issued, deposit-backed framework. For instance, if a global fintech firm requires a KRW-denominated stablecoin, a domestic bank could issue one based on its deposit holdings and offer it via API. These APIs could extend beyond simple remittance functions to include issuance and redemption of the stablecoin, transaction history, KYC status of users, and custody verification.

Through such infrastructure, fintech firms can integrate stablecoins into their services as a means of payment and settlement, or build automated reconciliation systems linked to user wallets. Importantly, this model operates within the regulatory perimeter of the banking system, enabling full compliance with deposit insurance and AML/CFT standards while allowing fintech providers to design flexible and user-centric experiences.

Banks, as issuers, can adopt a risk-based approach to control the circulation of the stablecoin, and further enhance scalability by linking on-chain payment APIs to their internal settlement networks.

This structure offers a pragmatic balance between institutional stability and technological scalability. It also demonstrates that it is possible to respond to private-sector innovation demands without affecting monetary issuance authority or macroeconomic policy transmission.

In contrast, policymakers remain cautious about non-bank stablecoins on public blockchains. Particularly in advanced financial markets like Korea—where infrastructure is mature and the unbanked population is minimal—claims of innovation based solely on the use of public blockchain technology are unlikely to justify systemic adoption.

JP Morgan and MIT DCI (2025) have highlighted that existing stablecoin architectures and ERC token standards still fall short of meeting the practical requirements of institutional payments. In response, their report proposes new token standards and smart contract design guidelines that embed regulatory-compliant features. Such global discussions offer a valuable reference point for Korea as it evaluates whether and how to adopt public blockchain–based payment tokens.

Given this context, a prudent strategy would be to first implement and validate bank-issued stablecoins that meet both technical and regulatory requirements. Consideration of public blockchain deployment can then follow—incrementally and in alignment with the maturation of global interoperability standards—thus balancing policy stability with market-driven innovation.

Moreover, relying on legacy private blockchain infrastructures such as Corda, Hyperledger, or Quorum is no longer tenable. Today’s technologies enable customizable architectures that blend privacy and openness, allow interoperability across private chains, and optionally connect to public networks. In other words, the paradigm is shifting toward hybrid infrastructures that flexibly support both institutional control and innovation.

To initiate a substantive policy discussion around public-chain stablecoins, proponents must present concrete business models, detailed circulation and settlement roadmaps, and robust technical implementation plans. Crucially, they must also demonstrate how such stablecoins can generate real liquidity and unlock novel use cases. Without such evidence, public-chain stablecoins may risk repeating the fate of JPYC on Uniswap—stuck in fragmented, shallow liquidity pools—and further undermine their institutional acceptability.

Ultimately, policy legitimacy does not stem from the argument that “it must be on public chains,” but from a clear articulation of the real-world demand they fulfill and the tangible economic impact they can create across industries.

3.3.2. Priority Areas for Blockchain Adoption

If deposit-backed stablecoins issued by banks become a core pillar of regulated digital liquidity, it also becomes clear where such stablecoins should be deployed first within financial infrastructure. This is not merely a matter of digitizing payment instruments, but a technological shift aimed at solving structural challenges such as inter-institutional trust coordination, cross-border asset transfers, and system interoperability.

In particular, in Korea’s highly centralized and advanced domestic interbank settlement infrastructure, the need and utility of blockchain may be limited. However, for asset and payment flows that cross borders, or for complex systems requiring interoperability between institutions, blockchain can serve as a powerful tool for efficiency and streamlining.

(1) Clearing and Settlement Networks

Deposit-backed stablecoins can be prioritized for application in cross-border payment and settlement infrastructures, including:

- Foreign Exchange (FX) Settlement: In interbank FX transactions, stablecoins can enhance settlement speed, automation, and certainty by replacing legacy processes that involve delays, high intermediation costs, and settlement risks. A smart contract–enabled Payment-versus-Payment (PvP) structure on blockchain can significantly improve efficiency.

- Reference – Project Jura

- Overview: A joint initiative by the BIS Innovation Hub, Banque de France, and Swiss National Bank. The project experimented with wholesale CBDC (wCBDC) to execute EUR-CHF FX settlement on a permissioned blockchain using automated PvP mechanisms.

- Milestone: Successfully completed in late 2021, the project demonstrated legally final settlement without relying on central bank RTGS systems.

- Key Outcome: Proved the viability of real-time FX PvP using smart contracts, with central banks playing only triggering and guaranteeing roles, not acting as settlement processors.

- Implications for Korea: In the Korean context, integration with BOK-Wire+ is essential to ensure finality. Since the Bank of Korea operates the RTGS system directly, a more active and direct integration model than Jura’s "trigger role" may be required. A similar structure can be developed using deposit-backed tokens instead of wCBDCs.

- Reference – Project Jura

- Trade Finance: Through permissioned and interoperable blockchain networks, it becomes feasible to automate conditional payment processes—such as those based on e-Letters of Credit (e-LC) or e-Invoices—between Korean banks and foreign institutions or corporates adopting similar technical standards.

- Reference – Project Guardian

- Overview: A public-private initiative led by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), this project demonstrated smart contract-based conditional payments using deposit-backed tokens. Although it did not directly target trade transactions, its programmable settlement capabilities are applicable to trade finance.

- Milestone: As of 2024, on-chain pilots for bond settlements and fund subscriptions have been successfully completed.

- Key Outcome: Validated the scalability and reliability of smart contract-based conditional payment systems.

- Implications for Korea: Integration with existing digital trade infrastructures (e.g., KTNET, K-SURE, Korea Eximbank) could enable automated settlement for B2B trade using deposit tokens. This is particularly beneficial for SMEs by enhancing payment certainty and reducing documentation burdens.

- Supplementary Insight – Lessons from Contour and TradeLens

- Explanation: Despite their technical sophistication, platforms such as Contour (e-LC via Corda) and TradeLens (digital bills of lading via IBM-Maersk) failed to commercialize due to limited participant networks and fragmented standards, not due to technological flaws.

- Implication: The key lies in network adoption, not just technology. Korea should coordinate with countries actively testing deposit token models (e.g., Japan), join global forums for interoperability, or consider launching its own collaborative platform.

- Reference – Project Guardian

- Cross-border RTGS Enhancement: Instead of fully replacing national RTGS systems like BOK-Wire+, a blockchain-based clearing and liquidity coordination layer can be added as a complementary structure, using stablecoins as settlement tokens.

- Reference – Project Agorá

- Overview: A multinational initiative launched by the BIS Innovation Hub, aiming to establish PvP settlement across different jurisdictions using both wholesale CBDCs and commercial bank-issued stablecoins, without requiring direct interconnection between domestic RTGS systems.

- Progress: Announced in 2024, involving nine global banks including Citi and JP Morgan, conducting multi-party FX settlement trials.

- Key Result: Demonstrated that while core RTGS systems remain intact, clearing, settlement instruction, and liquidity netting processes can be automated via smart contracts on blockchain.

- Implications for Korea: Final KRW settlements would continue via BOK-Wire+, but on-chain instruction processing and interbank liquidity netting using deposit tokens could enhance efficiency and interoperability in cross-border flows.

- Reference – Project Agorá

(2) Securities Clearing and Asset Management

Stablecoins backed by commercial bank deposits can also play a vital role in streamlining securities settlement and asset management infrastructure in capital markets:

- Securities Settlement: Korea’s current T+2 securities settlement cycle can be upgraded to T+0 using deposit-backed stablecoins in a Delivery-versus-Payment (DvP) structure. By integrating with central infrastructures such as KSD and KRX, a phased implementation of real-time DLT-based settlement systems can be achieved, accompanied by reforms in market practices and liquidity management frameworks.

- Reference – DTCC Project Ion & Smart NAV

- Overview: The U.S. Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC) is developing Project Ion, a permissioned DLT-based central clearing system designed to support T+0/T+1 settlement. Smart NAV enables real-time dissemination of fund Net Asset Value (NAV) on-chain, aiming to automate asset management and securities clearing.

- Progress: As of 2023, Project Ion operates in parallel with DTCC’s clearing systems, processing over 160,000 trades daily. Smart NAV is undergoing PoC with firms such as Franklin Templeton and Invesco.

- Key Results: Demonstrated that central clearing functions can be maintained while automating real-time settlement instructions and DvP operations via DLT.

- Implications for Korea: Existing infrastructure (KSD, KRX) can remain, but select features—such as T+0 settlement instructions and automated collateral transfers using deposit tokens—can be implemented on-chain. Initial use cases could include CMA, MMF, and ETFs, where real-time settlement is critical.

- Reference – DTCC Project Ion & Smart NAV

- Tokenized Asset Management (RWA Integration): By combining deposit tokens issued by institutions with tokenized real-world assets (RWAs), an on-chain asset management structure can be implemented that enables real-time settlement, collateral transfers, and NAV sharing. This infrastructure enhances accessibility to alternative investments (e.g., private equity, real estate), improves liquidity, and automates manual processes, thereby transforming the investment experience for both institutions and individuals.

- Reference – JP Morgan Kinexys

- Overview: Kinexys is an institutional digital finance network that integrates deposit tokens and the ODA-FACT token standard to automate asset management, payments, collateral transfers, and portfolio rebalancing within a single platform. It ensures transaction integrity and regulatory compliance (AML/KYC) without a central clearing party, and strengthens on-chain data privacy through Project EPIC (2024), which features private ledgers and identity verification services.

- Progress: Brand launch in 2024 with partnerships across global institutions such as Apollo Global, Citi, and WisdomTree. As of 2025, over $2B in assets processed daily through its real-time digital settlement infrastructure.

- Key Results: Real-time portfolio management and settlement using deposit tokens. The ODA-FACT standard supports T+0 asset exchanges and rebalancing, maximizing liquidity and operational efficiency. The regulatory-compliant structure (account locking, sanctions enforcement) builds institutional trust.

- Implications for Korea: Korean banks can issue deposit tokens to enable real-time settlement and asset exchanges for MMFs, ETFs, and real-estate funds. Public fund structures can adopt a standardized mint/burn process (e.g., ODA-FACT) under the upcoming STO platform regulation in 2025. Technologies such as Project EPIC's privacy and identity verification features will be necessary to comply with Korea’s privacy and capital market laws. Full smart contract automation with T+0 settlement will require infrastructure alignment with KSD, real-time NAV calculation via KRX data feeds, and regulatory clarity on security classification and collateral recognition.

- Reference – JP Morgan Kinexys

(3) Additional Potential Application Areas

- On-chain Securitization: By leveraging recurring cash flows and deposit-token-based structures, it is possible to design real-time ABS and ABCP issuance and redemption mechanisms using smart contracts. Especially for securitized products backed by overseas assets or multinational revenue streams, blockchain architecture offers clear advantages in terms of legal contract transparency, repayment traceability, and settlement finality.

- Efficiency in Cross-border Securities Settlement: For example, when Korean investors trade U.S. equities, the settlement process involves multiple intermediaries, resulting in delays and additional fees. By transitioning to an on-chain DvP settlement model using deposit-backed stablecoins, significant improvements can be made in settlement speed and operational efficiency. It also opens up possibilities for automatic dividend distribution and future on-chain direct investment via tokenized ADRs. However, integration with global custodians and institutions like DTCC, along with legal and tax coordination, remains a prerequisite.

These areas represent high value-added use cases where the limitations of the current system—cost, time, and risk management—are clearly evident. Blockchain can address these challenges structurally.

More importantly, by aligning with blockchain infrastructure already adopted by global financial institutions, Korea's digital finance ecosystem could become directly connected to international networks.

If Korea’s permissioned blockchain architecture evolves into an interoperable global standard, it could lead to direct connectivity with overseas financial institutions, enabling foreign exchange swaps, cross-border trade settlements, and co-issued digital securities. Ultimately, cross-border financial interoperability will become more than a technological choice—it will be a core strategic asset in the digital transformation of the national economy.

3.3.3. Required Technological Infrastructure

As the application areas for bank-issued deposit-backed stablecoins become clear, the technological infrastructure required to support their deployment must also be defined with greater specificity. The core requirement is to satisfy the essential conditions of regulated finance—regulatory compliance, transaction privacy, system control, and high-performance settlement processing—while simultaneously delivering the advantages of blockchain, such as on-chain automation and global interoperability.

The most promising approach is to implement a system of customizable permissioned blockchains, each tailored to institutional needs, while ensuring native interoperability among them. This allows for robust AML/KYC enforcement, regulatory-grade privacy, and high-throughput settlement, while still enabling connectivity with external chains when needed.

A representative example is the Avalanche Subnet architecture. This structure combines the controllability of private chains with interoperability, and offers the following key features:

- Access Control and Regulatory Compliance: Network participants are limited to pre-approved institutions or partners, and all transactions are executed only after undergoing KYC/AML checks.

- Data Privacy Protection: Real-name identities are not stored on-chain. Instead, the system follows a pseudonymous model that allows regulators to trace activity when necessary.

- Optional Public Connectivity: Subnets can optionally interoperate with the public chain or other subnets if desired.

SMBC is planning to issue a JPY stablecoin using an Avalanche Subnet, establishing a closed system where only approved partners are granted access. As this Japanese megabank begins live transactions of a Subnet-based stablecoin, it sets the stage for real-time testing of interoperability between JPY and KRW wholesale stablecoins, should Korea issue its own stablecoin in the same framework.

JP Morgan's Kinexys issues deposit-based tokens on its proprietary permissioned chain (Quorum-based), enabling the automation of specific financial activities such as FX trades, repo transactions, and securities settlements. While Kinexys has long operated on Quorum, it has recently begun exploring Avalanche Subnet’s privacy-enhancing features through Project EPIC. This involves integrating Avalanche technology modularly into specific domains such as portfolio tokenization. Notably, this is not a full migration of Kinexys infrastructure but a selective incorporation of Subnet modules.

Intain operates its structured finance platform, IntainMARKETS, on an Avalanche Subnet. The platform automates the issuance, investment, and settlement of ABS entirely on-chain and currently manages over $6 billion in assets. Built on a permissioned network compliant with AML/KYC and GDPR, it enables multi-stakeholder participation while reducing costs and issuance time for small-scale ABS, thus demonstrating the feasibility of blockchain adoption in structured finance.

In conclusion, bank-issued stablecoins are not merely payment tools but can evolve into critical infrastructure for the digital transformation of regulated finance. Connecting to public chains should be positioned as a long-term goal, contingent upon regulatory harmonization. For now, a realistic approach is to focus on infrastructure that supports wholesale payments, securities settlement, and international liquidity management within the regulatory framework.

3.4. Korea’s Strategic Response: Balancing Institutional Acceptance and Innovation

Korea’s policy approach to digital currency prioritizes institutional integration and policy control over rapid implementation. Specifically, the three pillars of monetary sovereignty, foreign exchange regulation, and financial stability demand a gradual adoption strategy led by the central bank and commercial banks rather than uncontrolled private-sector proliferation. Accordingly, Korea’s strategic response consists of the following three directions:

(1) Promoting Institution-Centric Stablecoins

- Establish a permissioned infrastructure centered on bank-issued, deposit-backed stablecoins, enabling coverage of both wholesale and retail payment use cases and laying the foundation for potential interoperability with international settlement networks.

- In alignment with global precedents, implement permissioned frameworks first, and consider optional interoperability with other systems as technical maturity and regulatory conditions evolve.

- Web3 partnerships should be introduced in a limited fashion via API or white-label structures to maintain institutional stability while selectively embracing innovation.

(2) Operating a Regulatory Sandbox for Conditional Flexibility

- After thoroughly analyzing potential impacts on monetary policy effectiveness, capital flows, and financial stability, experimental issuance by non-bank entities may be allowed within a limited and controlled scope.

- Such experiments must be conducted exclusively under the regulatory sandbox framework, with mandatory prior approval and post-reporting requirements for all aspects, including issuance volume, circulation boundaries, and redemption mechanisms.

- It must be clearly stated that this measure is intended to enhance institutional responsiveness to technological change, and should not be interpreted as an endorsement of widespread non-bank stablecoin adoption.

(3) Global Alignment and Technical Standardization

- Korea should reference major international policy frameworks, such as the GENIUS Act (U.S.), EU MiCA, and Japan’s bank-led models, to establish functional distinctions and interoperability standards among CBDCs, deposit tokens, and private stablecoins.

- This approach will help create touchpoints between Korea’s institutional financial system and the global Web3 ecosystem, forming the basis for a long-term transition to an integrated digital payment infrastructure.

In conclusion, a bank-issued, permissioned stablecoin model presents the most feasible and institutionally acceptable strategy for digital currency adoption in Korea. This model can support efficient cross-border financial transactions, ensure interoperability among institutions, and enable the compliant circulation of digital assets. In contrast, non-bank issuance structures should remain confined to regulatory experiments, with Korea’s overall strategy remaining rooted in a two-tier currency system led by the central bank and commercial banks.

- An Overview of Japanese Stablecoin Regulation by DK

- Stablecoin Market and Regualtions in Global: An Overview by Sose

- The Evolution of Stablecoins: New Opportunities and Challenges by Sose

- Analysis of Supplementary Measures for Algorithmic Stablecoin Model by Do Dive

References

- Byron Gilliam, The stablecoin dilemma

- 김영식, CBDC, 스테이블코인과 통화제도

- DK, Twitter